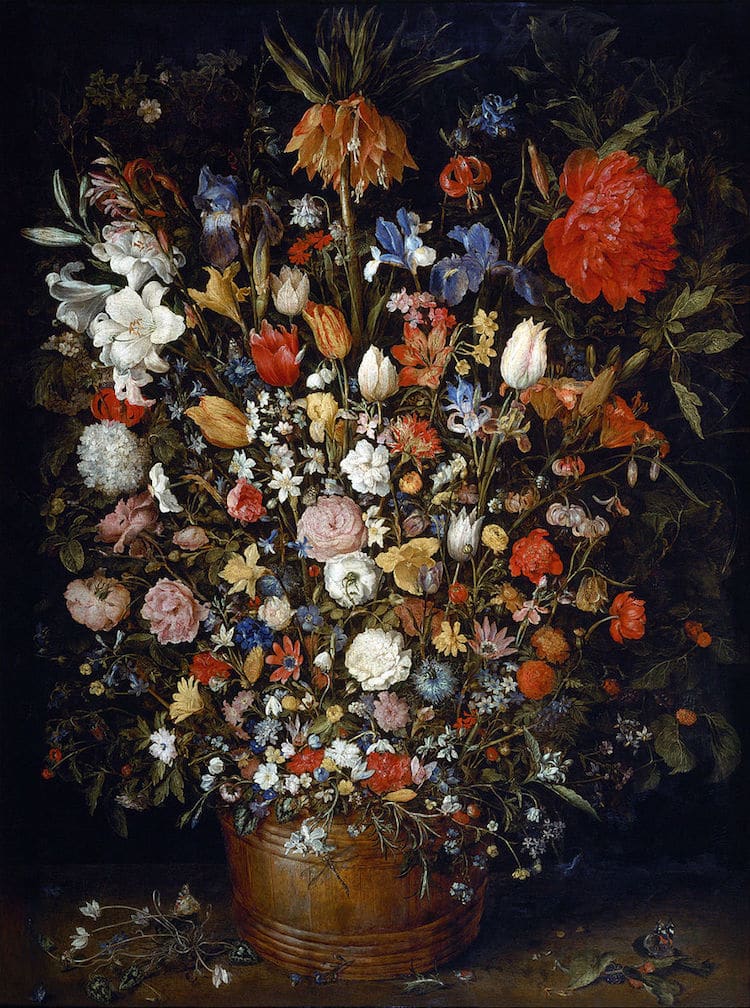

Claes Oldenburg & Coosje van Bruggen, Corridor Pin Blue, 1999, stainless steel, aluminum and glazed acrylic enamel (de Young Museum, San Francisco) |

|

So, I was reading about outdoor sculpture gardens and some of their lovely, harmonious artistic offerings to nature. Then I thought of our local de Young Museum's sculpture garden which is just off its cafeteria. You buy your food, take it on its tray to a table along the greenery, hear the birds chirp and look out to view ... a huge safety pin.

Not harmonious, but that was just fine and had been long before its creation in 1999 with its team of artists, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen. In 1961 Oldenburg wrote in his poem

I Am For Art "I am for an art that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum." And later in the poem 'I am for an art that you can hammer with, stitch with, sew with, paste with, file with. I am for an art that tells you the time of day, or where such and such a street is. I am for an art that helps old ladies across the street....."

By the time he wrote all this Oldenburg was studying art at Yale and totally fed up with the freeform wholly personal meditations on canvas of the Abstract Expressionists. He was one of several artists in England and then primarily New York and California who felt that art was not something separate and exalted from real life and began to celebrate real life with their "Pop Art" as it came to be called. They turned to everyday sources the most famous of which are probably Andy Warhol's Campbell Soup Cans.

Oldenburg, who later teamed with his wife, van Bruggen turned to sculpture and became known for his huge public sculptures. Among their creations are

shuttlecocks in Kansas City

a clothespin in Philadelphia,

and, one of my personal favorites, a spoonbridge with cherry in Minneapolis

.

Are they as impressive as a tree or just the green grass they sit in or as miraculous as the birds singing around them? No, but in their ways, they do respect the environments they are set in. There's a grace to their forms and a quietness to their simple designs and minimal colors. The joy and tongue-in-cheekiness is timelessly fresh. And from my experience giving private art tours, they make people happy.

*A nod to Joyce Kilmer's poem, Trees, which ends with the line "But only God Can Make a Tree."

.jpg?mode=max)

.jpg/150px-Philadelphia_City_Hall_with_William_Penn_(and_Clothes_Pin).jpg)

.jpg/1280px-Raphaelle_Peale_-_Still_Life_with_Cake_(1818).jpg)