"Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to release it"

"I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set it free."

~ Michelangelo (Italian, 1475-1564)

Having spent a few days at the de Young Museum in 1900's of Calder and Picasso, both of whom are celebrated for their sculptures, my thoughts now move to arguably (if anybody actually would) the greatest sculptor who ever lived: Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, best known simply as Michelangelo. And to a few things I learned about him recently.

First, biographically, I didn't know that he grew up, after the death of his mother, with his nanny and her husband who was a stone cutter. Or that Michelangelo's father owned a marble quarry so that the young boy spent a great deal of time watching stone being quarried and carved as well as acquiring hands-on experience with the stone at an early age. He also sought out the company of significant artists and worked in his early teens as an apprentice to one of the master painters who had been hired by the Vatican to decorate the walls of the Sistine Chapel.

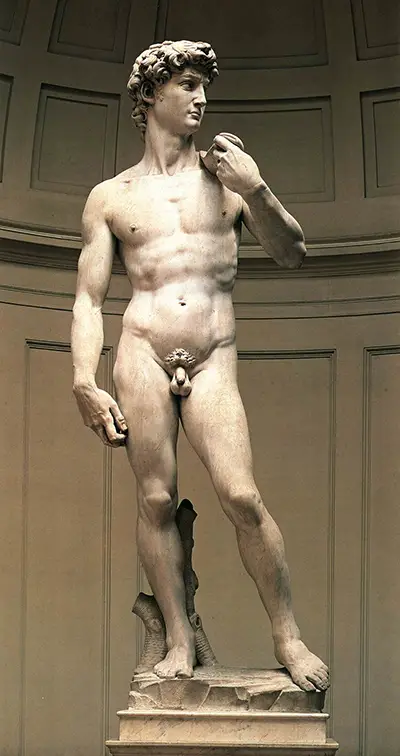

Second, in terms of his technique. Like many people I am familiar with the two famous quotes from Michelangelo above. Because of them I have carried an image of the sculptor standing in front of a block of marble and artfully chipping away until he began to sense a presence inside. And then gradually, carefully, laboriously continuing until, OMG, David! Or, secondarily, that Michelangelo looked at a block of marble, sensed what figure was in it, and carved away "until he set it free." In both cases, the figure inside would have been a revelation to Michelangelo.

Turns out, yes, Michelangelo saw sculpture as the art of taking away to bring the form below into existance. But, no, the look of the form was not a surprise to him. Even before, and certainly in the multi year process of actually carving, he produced detailed sketches - over 900 of them remain. The drawings are imbued with technical skill but, beyond that, with his own spiritual passion and desire to work with the marble to bring the soul of his subject to life.

No higher goals for himself can be imagined, and the wonder is that he actually achieved them - at an early age. During his twenties! he produced two of the world's greatest sculptural masterpieces, Pieta and David. At the time the life and emotion he had brought to the grieving mother and the depiction of the human form he achieved with David were beyond ground breaking, beyond a revelation. Nearly 450 years after his death in 1564 his work is as wondrous as it was at the time, remains ground breaking and is still the gold standard sculptors aim for.

|

| Micheangelo, Pieta, 1498-99, Carrara marble and then the very next year he began David |

|

| Michelangelo, David, 1501-1504, Marble |